CLPS - The Start of the Lunar Economy?

Private companies are setting up shop on the surface of the Moon

With recent, and continuous, delays to NASA’s Artemis program, humans are years away from once again stepping foot on the Moon. For decades, U.S. presidents, starting with George H.W. Bush, have been harping on the need to return to the Moon, with plans for a continued presence and the creation of an economic zone beyond Earth orbit. Yet still, we wait longingly for our lunar outposts, ISRU processing facilities, and radio observatories on the far side of the Moon. Despite the lack of progress on human lunar exploration, NASA has somewhat quietly been funding a program to spur commercial opportunities on the Moon, continuing it’s recent trend of turning to public-private partnerships to expedite schedules and lower costs.

The Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative or CLPS (pronounced “clips”), is a set of NASA task orders that offer quicker acquisition of delivery services for both civil and commercial payloads to the surface of the Moon. CLPS is an indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity (IDIQ) funding vessel with $2.6B of contracting power allocated through 2028. To date NASA has spent just north of $660 million of that allotment on seven missions, set to start later this year.

Where it All Started

Since the Soviet Union’s intentional hard landing (aka crash) of the Luna 2 spacecraft in 1959, 8 nations have launched roughly fifty missions that successfully landed on the Moon. NASA has touched down on the Moon eleven times between its uncrewed Surveyor and crewed Apollo programs. Russia has landed eight times and China three times (most recently in December 2020 with its Chang’e 5 program). In total, humans have dispensed an estimated 413,000 pounds of material to the Moon (equivalent to roughly 100 Tesla Model 3’s)!

The end of the United States’ Apollo program and Soviet Union’s Luna program in the 1970’s ushered in nearly four decades without a Moon landing of any kind. Hoping to end this drought, in conjunction with Google, entrepreneur Peter Diamandis introduced the Lunar XPRIZE competition in 2007. The challenge offered $20 million to the first (and $5 million to the second) privately funded team to successfully land a rover on the Moon, travel 500 meters, and transmit high definition videos and images back to Earth. Over the course of its 11-year tenure, the Lunar XPRIZE attracted 33 teams from around the world and by 2018, five teams remained. SpaceIL (Israel), Moon Express (USA), Team Indus (India), Team Hakuto (Japan), and Synergy Moon (Global) all secured flight contracts, but failed to meet the 2018 prize deadline, leaving the $20 million bounty unclaimed.

While failing to find a winner or land a spacecraft on the Moon, the Google Lunar XPRIZE created a ripple effect in the space industry. In 2019, in partnership with the Israeli Space Agency, SpaceIL became the first private company to attempt a lunar landing. Known as Beresheet, the lander traveled 239,000 miles to the lunar surface before experiencing a gyroscope failure, causing the main engine to prematurely shut down, eventually leading to an unsuccessful crash landing. Despite its explosive ending, SpaceIL was the first in a wave of commercial companies to make their lunar ambitions a reality. Now, former XPRIZE contestants and a slew of new entrants funded through NASA’s CLPS program have their sights set on creating a commercial marketplace on the Moon.

CLPS Contenders

NASA’s CLPS program picked up where the XPRIZE ended, encouraging commercial companies to partner with NASA to improve schedule and cost compared to historically bloated government programs. In 2018, the first nine companies were selected to bid on CLPS missions.

Tranche 1 (November 2018): Astrobotic, Deep Space Systems, Draper, Firefly Aerospace, Intuitive Machines, Lockheed Martin, Masten Space Systems, Moon Express, OrbitBeyond

Tranche 2 (November 2019): Blue Origin, SpaceX, Tyvak, Sierra Nevada, Ceres Robotics

Of those in the initial group, the first CLPS task orders were awarded to Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines, and OrbitBeyond in 2019. Later that year, OrbitBeyond forfeited their $97 million contract due to internal corporate conflicts. In November 2019, NASA onboarded five additional companies including Blue Origin and SpaceX. In the last two years, Masten Space Systems and Firefly Aerospace won their first CLPS awards while Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines were selected for follow-on flights.

Now, a bit more on the CLPS companies shooting for the Moon.

The Landers

Astrobotic

Lander Name: Peregrine and Griffin

Expected Launch: Q2 2022 (Peregrine), November 2023 (Griffin)

Landing Zone: Lacus Mortis (Peregrine), Nobile Crater (Griffin)

Payload Capacity: 100 kg (220 lbm) (Peregrine), 500 kg (1100 lbm) (Griffin)

Launch Vehicle: Vulcan (Peregrine), Falcon Heavy (Griffin)

Overview

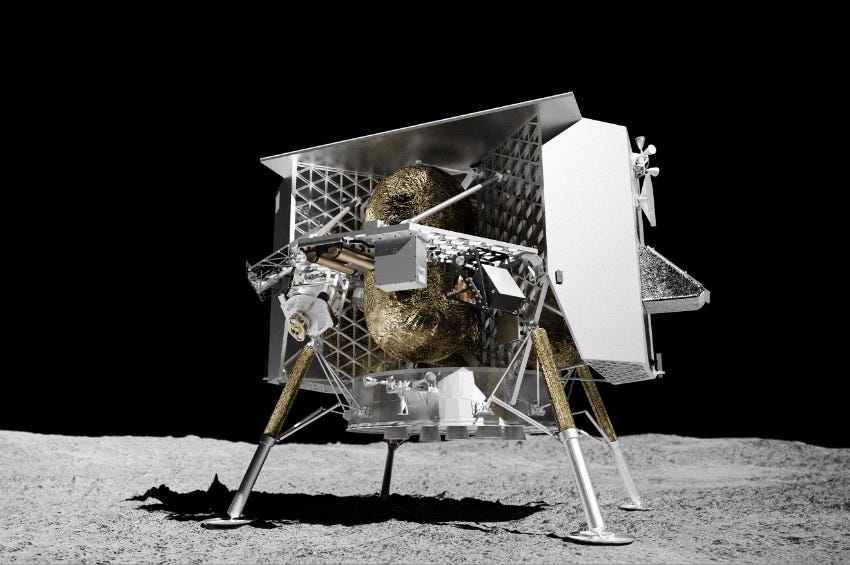

Based out of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania and originally spun out of Carnegie Mellon University by Professor Red Whittaker, Astrobotic is developing a family of lunar landers. Peregrine will be the smaller of the two landers currently in development. Standing roughly six feet tall, Peregrine is capable of carrying 100 kg to the surface of the Moon, landing with a Doppler LiDAR system, and deploying or hosting payloads on several attach points. As far as lunar landers go, Peregrine is relatively simple with an aluminum truss structure and reliable hypergolic MON-25/MMH landing engines built by Frontier Aerospace. That being said, Peregrine will check off a lot of “firsts” when it launches as the initial CLPS mission sometime in the coming months (the launch was originally scheduled for Q4 2021). If all goes according to plan, Peregrine Mission 1 will be the inaugural payload on ULA’s new Vulcan rocket, the first commercial lander from the United States, and the first soft landing on the Moon for the U.S. since Apollo. The Peregrine spacecraft will also carry 33 payloads for more than 13 countries to the surface of the Moon, many of whom will be making their lunar debuts with Astrobotic.

Building off of the initial Peregrine launches, Astrobotic is also building Griffin, its larger lander and primary offering to NASA and commercial customers. Griffin utilizes a similar avionics, communications, and structures scheme to Peregrine but is almost twice as wide and can carry five times the payload to the Moon’s surface. Additionally, Griffin uses five upscaled engines from Frontier Aerospace and a suite of RCS thrusters from Agile Space for attitude and axial control. In June 2020, Astrobotic was awarded $199.5M from NASA to deliver VIPER, a NASA-designed rover built to search for volatile materials in permanently shadowed regions of the Moon’s South Pole.

Intuitive Machines

Lander Name: Nova-C

Expected Launch: July 2022 (IM-1), Late 2022 (IM-2) Early 2024 (IM-3)

Landing Zone: Mare Serenitatis and Mare Crisium (IM-1), Lunar South Pole (IM-2), Reiner Gamma (IM-3)

Payload Capacity: 130 kg (286.6 lbm)

Launch Vehicle: Falcon 9

Overview

Based in Houston, Texas, Intuitive Machines is developing their Nova-C lander as part of the CLPS program. Intuitive Machines plans to launch their first mission, IM-1, in July of 2022 to an undisclosed area between Mare Serenitatis and Mare Crisium, similar to the Beresheet mission. Once there, it will deploy several payloads including five instruments for NASA. Interestingly, Nova-C borrows much of its technology from NASA’s Project Morpheus which ran from 2010-2015 and aimed to manufacture a cost-efficient lunar lander capable of vertical take-off and landing on rugged terrain. While the Nova-C lander is significantly smaller than the proposed Project Morpheus spacecraft, it uses similar guidance, navigation, and computer vision technologies to allow for autonomous landing on the lunar surface.

Unlike many of its competitors, the Nova-C lander uses liquid oxygen and methane propellants in preparation for one day utilizing in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) to create its own fuel on the Moon or Mars. Perhaps one of the most unique features of Intuitive Machines’ plan is the µNova “hopper” which will be deployed on Intuitive Machines’ second mission, IM-2. The µNova spacecraft is essentially a miniature version of the Nova-C and can travel up to 25km away from the main lander to explore difficult to reach areas such as caves and craters. IM-2 is set to launch in late 2022 and, if successful, will be the first soft landing at the Moon’s South Pole where it will release the PRIME-1 drill for NASA, intended to search for subsurface water and ice.

Masten Space Systems

Lander Name: Xelene (XL-1)

Expected Launch: November 2023

Landing Zone: Haworth Crater (South Pole)

Payload Capacity: 100 kg (220 lbm)

Launch Vehicle: Falcon 9

Overview

Masten Space Systems out of Mojave, California is a staple name in the NewSpace world, having built and tested a plethora of impressive engines and launch vehicles for the past two decades. In 2009, Masten first made a name for themselves by winning NASA’s Lunar Lander Challenge with their Xombie and Xoie vehicles. The challenge required teams to design and manufacture a vertical take off, vertical landing (VTVL) spacecraft to fly 50m vertically and 100m laterally for more than 180 seconds before landing on a simulated lunar surface. The vehicle was then refueled and had to return to its initial launch site.

Since then, Masten has designed a fleet of vehicles including Xaero and Xodiac (starting to notice a naming pattern?), with Xogdor and Xeus designed for future proposals. In total, Masten has completed over 600 rocket powered vertical landings on an assortment of vehicles and engines using various propellants. I could write a whole article on the quirky, brilliant folks at Masten and the rockets they’re building, but this one will focus on their Xelene lunar lander.

Xelene builds on the legacy of Xombie and Xoie with similar overall structure and landing mechanisms. The vehicle utilizes 6 main Machete engines and 12 RCS thrusters that burn Masten’s proprietary MXP-351 hypergolic bi-propellant fuel combination. Xelene will carry 8 payloads to the Lunar South Pole for NASA, university researchers, and commercial customers like Maxar and Ball Aerospace. Despite their storied past, Xelene is set to be Masten’s first space mission when it launches in late 2023. Masten is also pioneering its in-Flight Alumina Spray Technique (FAST) technology which injects aluminum particulates into Xelene’s engine exhaust to create an ablated landing pad below the vehicle. This will help Xelene and other lunar landers avoid the potentially detrimental effects of abrasions from high-velocity lunar regolith when approaching the surface of the Moon.

Firefly

Lander Name: Blue Ghost

Expected Launch: Mid 2023

Landing Zone: Mare Crisium

Payload Capacity: 150 kg (330 lbm)

Launch Vehicle: Falcon 9 (for initial flights)

Overview

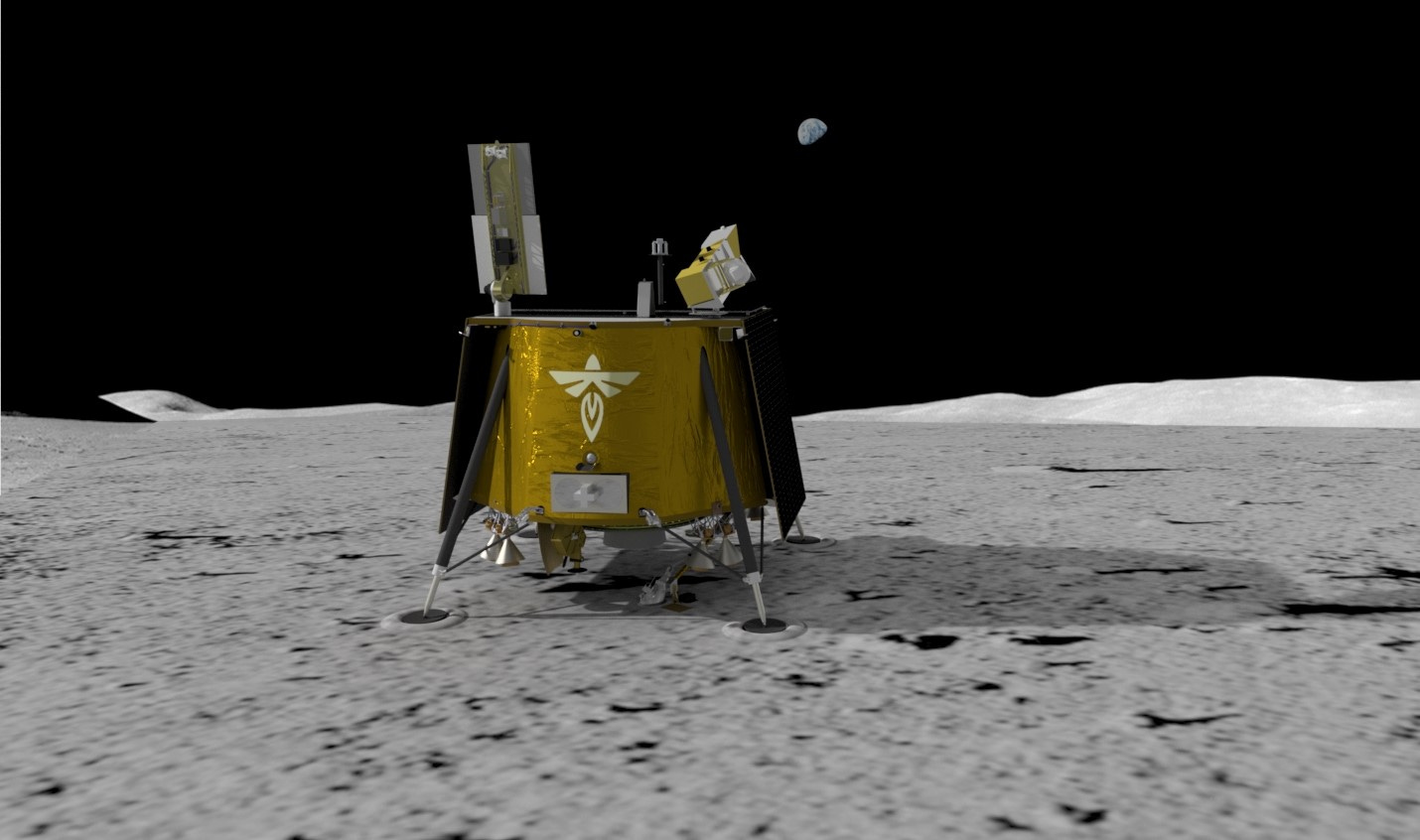

While mostly known for their launch vehicles and foreign ownership conflicts, Firefly Aerospace out of Cedar Park, Texas has been quietly developing a lunar lander and was awarded their first CLPS mission in February 2021. Known as Blue Ghost, the lander is expected to carry up to 150kg to the lunar service and Firefly envisions yearly missions as part of their network of space transportation vehicles including their Alpha (and eventually Beta) rocket and their Space Utility Vehicle tug.

Not much has been publicly disclosed about Blue Ghost but the users manual does mention steerable solar panels, secure communications networks in partnership with Swedish Space Corporation, and a suite of options for payload accommodations and deployments. While not disclosed, it is likely that Firefly is developing their engines in-house given their history of vertically integrating propulsion for their launch vehicles. Blue Ghost’s first CLPS mission is scheduled for Mid 2023 and will target the Mare Crisium basin where it will deploy 10 NASA-sponsored payloads and scientific instruments.

The Rest of the Bunch

You may be wondering, “Where’s SpaceX? Blue Origin? Aren’t they building landers?”

SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Dynetics were the finalists for NASA’s Human Landing System (HLS) program which will be a part of the larger Artemis architecture to bring humans back to the Moon by (hopefully) 2025. SpaceX was sole selected for the $2.9 billion contract despite protests from both of its competitors and is now working to provide a lunar variant of its Starship vehicle to integrate into the Artemis program alongside NASA’s Space Launch System and Lockheed Martin’s Orion spacecraft. Despite failing to win a part of the initial HLS contract, Blue Origin is continuing work on its Blue Moon lander for future follow-on cargo delivery missions and may even compete on future CLPS mission contracts. It’s worth noting that the HLS proposed landers are much larger than the CLPS commercial landers. For comparison, where Firefly hopes to carry up to 150kg to the Moon, Blue Origin’s Blue Moon is offering up to 4500kg!

Another growing company in the lunar ecosystem is iSpace, spun out of the original Japanese-based Team Hakuto from the Lunar XPRIZE. iSpace is developing their Series 1 and Series 2 landers to launch by 2024 and will represent Japan’s first lunar landing. They are also planning to deploy their SORATO lunar rovers on some of the earlier CLPS missions. iSpace is hoping to lead the charge on creating a Moon base and spurring the future of a lunar economy with a focus on government and commercial customers. It is very likely that iSpace (and their US-based subsidiary) will be included in the next onboarding of CLPS missions.

There are other players in the field including remnants of original XPRIZE and CLPS providers like Moon Express and OrbitBeyond and mainstays like Northrop Grumman and Sierra Space. It is clear that companies are taking plans for the Moon seriously and I wouldn’t expect anything to slow down in the coming decade as the US, Europe, Russia, and China look to create permanent footholds on Earth’s only natural satellite.

What’s Next?

For decades, scientists, Sci-Fi writers and entrepreneurs have been turning their sights towards the Moon as the next great frontier. Despite several failed government initiatives to try and return humans to the Moon, NASA now seems determined to follow through on the Artemis missions to create a robust lunar ecosystem. The first step in this plan is funding commercial companies like Intuitive Machines, Astrobotic, Masten, and Firefly to demonstrate the commercial viability of a Moon mission while simultaneously deploying critical NASA assets in anticipation of future legs of the Artemis proposal. These CLPS task orders will provide key information about landing zones and surface conditions that will pave a path for US astronauts to take another giant step for mankind.